When U.S. Senators Rob Portman (R-OH), James Langford (R-OK), Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Richard Durbin (D-IL) co-sponsored a bipartisan resolution declaring April as Second Chance Month, it was welcomed and embraced by a broad coalition of civil rights groups and progressive and conservative criminal justice reformers. This year, at least eight states, the District of Columbia, and two local jurisdictions joined President Donald Trump in recognizing April as Second Chance Month. The movement aims to help people who have paid their debt to society return to something closer to normal citizenship—and it is growing in both breadth and substance.

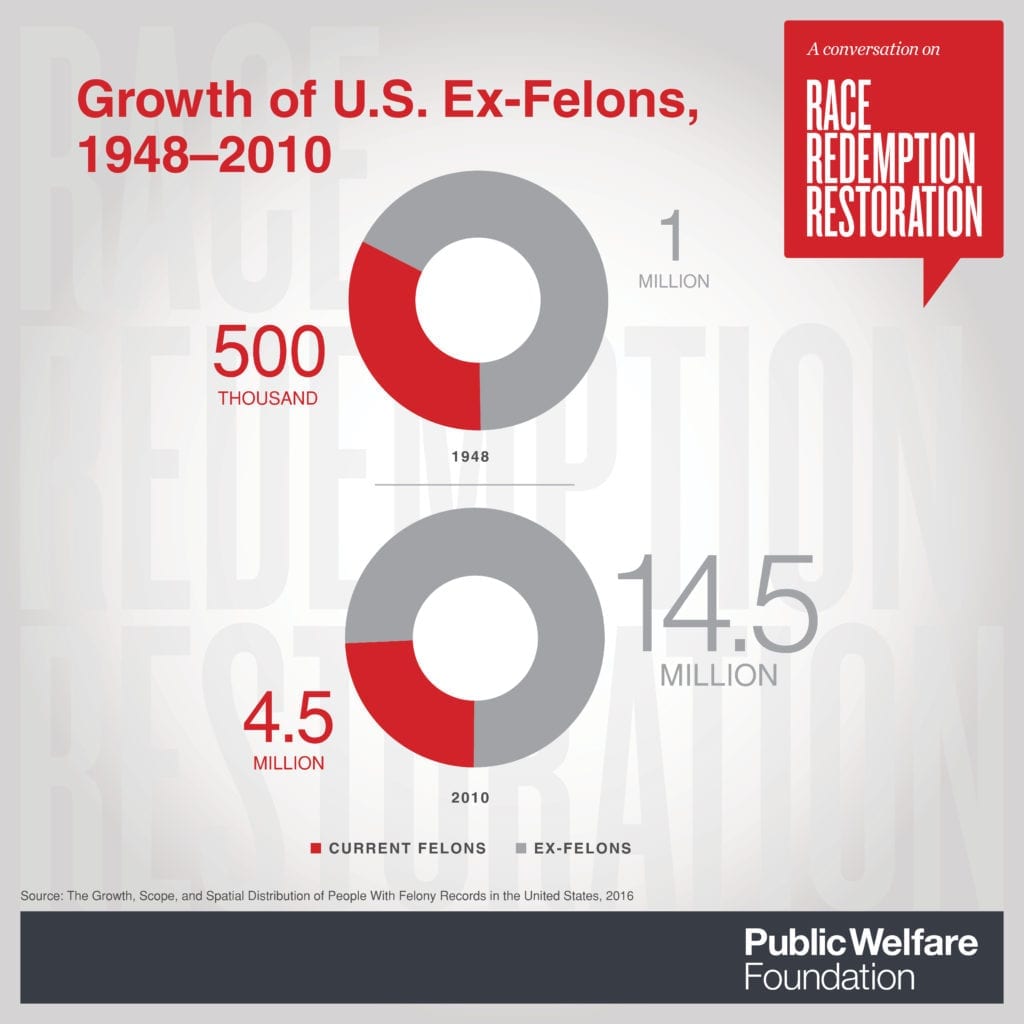

While the U.S. incarcerates 2.2 million people in its prisons and jails, about 65 million people have been convicted of a crime, and about 30 percent have served time in prison. With approximately one in four Americans having a criminal record, the consequences can be overwhelming.

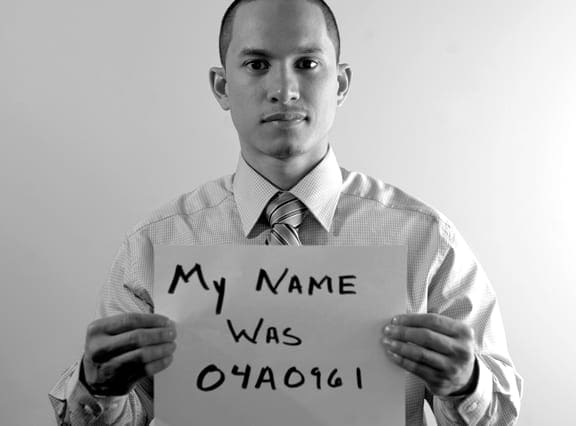

As Jay Jordan, Second Chances Project Director for Public Welfare Foundation grantee Californians for Safety and Justice(CSJ), puts it so poignantly in the accompanying video, having a criminal record is like “wearing a big ‘F’ on your chest” and “like someone holding you under water.”

That’s because the ripple effects of being involved in the justice system are enormous. For starters, 10 states still prohibit people with convictions from voting. Beyond that, research shows that people with convictions and those who have been incarcerated have difficulty finding employment or decent housing or pursuing an education. Too often, they are unable to provide for or even make a meaningful contribution to the welfare of their families. Many end up homeless and/or impoverished.

Prison Fellowship, another Foundation grantee, and the driving force behind Second Chance Month, provides extensive outreach to prisoners, former prisoners, and their families. It calls such limitations on those with convictions, a “second prison,” and it has documented more than 48,000 social stigmas and legal restrictions that “inhibit building full, productive lives after paying a debt to society.”

The nation cannot just pay lip service to the idea of providing opportunities for those coming out of prison or dealing with felony convictions to fully redeem themselves. As a society, we need to be more deliberate in helping those with criminal records and the communities to which they either return or resettle.

In 2014, former prisoners comprised an estimated 6 to 6.7 percent of the working-age male population, and people with felony convictions comprised 13.6 to 15.3 percent, according to a 2016 report by the Center on Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) on the economic costs of employment barriers for former prisoners and people with felony convictions.

Another study in 2010 on the effects of incarceration on economic mobility calculated that, in 2008, people who had been in prison accounted for the loss of between 1.5 million and 1.7 million workers from the U.S. economy, at an estimated cost of $57 billion to $65 billion in gross domestic product (GDP) per year.

Incarceration also takes a devastating toll on women, whose numbers have increased in state and local prisons and jails since the late 1970s, according to a report by grantee Prison Policy Initiative. And, Andrea James, Founder and Executive Director of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, a Foundation partner, notes that incarcerated women, like men, also need to regain skills and schooling in order to take care of themselves and their families once they return home.

Now, in a robust job market, businesses are reaching out to train and employ people who are still in prison or out of prison, as well as those with criminal records. Colorado’s Work and Gain Education and Employment Skills (WAGEES) program, in which Foundation grantee Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition plays a prominent role, uses state resources for grants to community-led organizations that provide various services to help people coming out of prison get jobs or go to school. And the U.S. Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell program offers financial aid to incarcerated individuals for high quality education. Foundation grantee Vera Institute of Justice is trying to educate Congress on the benefits to individuals, families, and society if Second Chance Pell grants can be extended and expanded.

But even more can be done. The U.S. could follow the examples of the United Kingdom and Portugal, which allow records of certain crimes to be expunged after designated rehabilitation periods. Once those rehabilitation periods have passed with no additional convictions, the original conviction falls under a sunset clause and would not have to be disclosed on job or insurance applications, in civil proceedings, or in other instances.

California could become the first state to take a similar approach. One bill being considered by the State Legislature would expeditiously expunge a conviction after an individual successfully completes probation. And another bill would prevent the state’s Department of Justice from reporting expunged convictions after an individual has been crime-free for seven years.

“These bills will help about eight million people in California regain full citizenship and, essentially, their humanity,” declared Jordan. “That makes the idea of giving people with criminal records ‘second chances’ even more meaningful.”